You are currently browsing the monthly archive for January 2016.

Leaving Antarctica is no small feat. We have to break down and store the contents of an entire laboratory (that we set up just weeks earlier). Some items are returned to the Crary Laboratory stockroom, others are put in boxes for “the line” (overwinter storage in big wooden boxes that are kept outside, so things inside must be okay to freeze), extra chemicals are stored in the LTER lab, and finally, the most fragile items are moved into the cage (small locker-like cage that is indoors, so microscope accessories and other fragile items are kept here).

Example of a box “from the line.” These boxes are filled with our laboratory and sampling equipment and stored outside over the winter. Photo by: Matt Knox

Samples must be prepared for shipment, a process which includes packing, weighing, measuring and labelling boxes, and grappling with an electronic shipping system that is still based on the MS software Access. It’s not only the organisms that live long in Antarctica!

Once everything is packed away, we have to clean – lab space, office space, and our own dorm rooms. Then, these rooms must pass inspection or we have to clean again.

Walter boarding “Ivan” the Terra Bus for transport. Photo by: Jessica Trout-Haney

Finally, the evening before leaving, we take our own bags to be checked in for our flight. This process is literally officially called “bag drag.” At this time, we find out our transport time for the next morning (it can take over an hour to just get to the plane, so we have to arrive at this time for transport to the airplane). For the last night in McMurdo, you only have your carry-on bag with you – better remember to keep your toothbrush!

Written by: Ashley Shaw

From the time we arrive in Antarctica to the time we depart, we hurry around working to obtain our samples, get them processed, collect good data, and get the samples prepared for shipping home. Then it’s packing, cleaning, and rushing to get on a plane. The whole month is a whirlwind of science. It’s a blast, but it’s also exhausting.

The C507 Soil Team in front of the Crary Lab. From left to right: Jessica Trout-Haney (Dartmouth), Dan Bransford (Virginia Tech), Summer Xue (Brigham Young), Tandra Fraser (Colorado State), Diana Wall (Colorado State), Walter Andriuzzi (Colorado State), Ashley Shaw (Colorado State), Jeb Barrett (Virginia Tech), Ruth Heindel (Dartmouth), and Byron Adams (Brigham Young).

I’ll give you the overview of what we did this season: In summary, we sampled five core studies at six different sites, applied treatments to two core studies at three sites, completed lab work on 420 soil samples, serviced meteorological stations, collected samples from aeolian (wind-blown) sediment collectors, and collected additional soil samples from multiple locations for our work in labs back home. Mixed in with this work are repairs to equipment, weather delays, establishing proper communications at field sites, and ensuring work is done in a safe way that preserves the Antarctic environment.

Diana Wall takes a soil sample near Marr Pond in Taylor Valley. Photo by: Ashley Shaw

The first priority for work is sampling core studies, which are critical to the NSF Long Term Ecological Research program’s mission. So, on nine different trips (both overnight and day trips), we went to the McMurdo Dry Valleys via helicopter to sample our core experiments and long-term study sites. These included the Stoichiometry Experiment, the P3, the Elevational Transects (read about these here or here), the LTM, and the controls from the BEE plots. We bring these soil samples (each one weighs about 500 grams) back to the lab for processing (you can read about our soil extraction process here). Once the nematodes and other critters have been extracted, we use a microscope to help us identify and count every individual animal from each sample. Not only do we study which species are present, but also details about their life history, including their sex and whether they are alive or dead. This gives us information about community trends. At the same time, we are performing soil chemistry measurements to evaluate soil carbon, pH, salinity, phosphorus, and nitrogen. These chemistry data help to indicate which environmental conditions are most (or least!) suitable for life. We also extract and measure chlorophyll-a as a proxy for primary productivity.

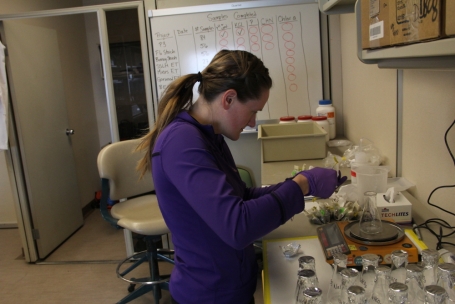

Jess weighing soil for soil chemistry analyses. Photo by: Ruth Heindel

Besides sampling these experiments, we also have to apply treatments to some of the core experiments. This year, we applied treatments to the P3 and the Stoichiometry Experiment. The P3 treatment took place over a couple days, and required Byron, Jeb, and Dan to stay at F6 camp and walk to the experimental plots. You can read about the treatments (here), but in short, this treatment involves pumping water up from Many Glaciers Pond, sterilizing the water, and pumping the water down slope at the subsurface to simulate melt flowing over the permafrost. The Stoichiometry Experiment requires nutrient treatments to be prepared in the lab (you can read about that here), this then requires hauling ~30 carboys filled with nutrient solutions (about 5.6 liters in each carboy) out to our experimental plots and applying those solutions.

Byron carries carboys full of nutrient solutions to the Stoichiometry Experiment plots in Taylor Valley. F6 camp in the background at right. Photo by: Walter Andriuzzi

We went out on a few more day trips to put in new batteries and check on our meterological stations, take samples from and repair aeolian sediment collectors, and to collect some more samples to take back to our labs at home (for individual projects such as PhD or Masters projects).

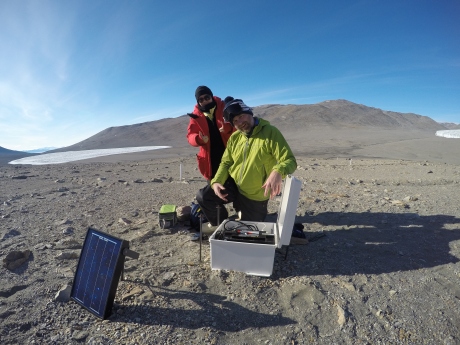

Summer and Byron are happy that the meteorological station in Miers Valley is now fixed and working! Photo by: Ashley Shaw

We are happy scientists –we had great weather with very few delays, our samples are ready to ship home, and all of the data has been collected for this season.

Mission complete!

Written by: Ashley Shaw

This is a story about living in McMurdo, told in 3 separate parts. This third and final installment of “A day in the life” will focus on another common question I get about Antarctica: What’s it like where you live?

A line of dorm buildings in McMurdo Station. Photo by: Ashley Shaw

We live in dormitories in McMurdo and have anywhere from 1 to 3 roommates depending on the building arrangement. Luckily, I am sharing a room with another wormherder, Tandra, which is great because we work on the same project and share the same schedule. Others aren’t so lucky and share their rooms with roommates who work in different departments, keeping much different hours and schedules. When you have a roommate who has a totally different schedule from you, this is very tough because you both end up interrupting each other’s sleep – making for a very tired season.

There are 16 buildings that are considered dormitories, but most of us end up in 203, 206, 207, 208, or 209. Each of these buildings has a lounge area with a TV and sometimes a pool table or an area to play games and hang out. Sometimes we go there after working to watch a movie or hang out, but most of the time we go straight to bed, exhausted from a long day of working. There is a 24-hour quiet policy in the dorms to allow for rest, so the lounges are a good place to chat so as to not disturb others who may be working different shifts or are on different sleep schedules. There are also laundry facilities in some buildings, shared bathrooms, and sometimes even a sauna. One dorm has a library where you can check out books.

A typical dorm room in McMurdo has 2 twin beds, 2 wardrobes, 2 small chest of drawers, and a desk. Photo by: Ashley Shaw

The dorms are not hotels and there are no maids in McMurdo, so each of us has to contribute to keeping our dormitories clean. We perform weekly duties called our “House mouse” chores. This could be anything from taking out the trash, tidying up a lounge, vacuuming the lounge, cleaning the laundry room, or vaccuming the halls. Last week, Tandra and I swept, vacuumed and mopped the front entryway and stairs of our dorm building for our House Mouse duties.

Ashley doing her ‘house mouse’ chore for the week. Photo by: Tandra Fraser

If you forgot something from home or you want to buy some souvenirs, the station store is open for a few hours on most days. They sell snacks, toiletries, t-shirts, hats, stickers, and other goodies. You can also check out movies to watch and they have a pretty big selection. Overall, many of the comforts of home are available on station, but of course, it takes place in a community setting that leaves many of us feeling like we’re back in college.

Written by: Ashley Shaw

This is a story about living in McMurdo, told in 3 separate parts. This second installment of “A day in the life” will focus on one of the most common questions I get when I tell people about my work in Antarctica – What do you eat? So here it is: eating in McMurdo – where, what and when.

While on station we eat three meals a day in the Galley. The meals are served in a buffet style, but there are two grills where you can sometimes get a burger or eggs cooked how you like. Cereal, coffee, tea, pizza, cookies, and popcorn are available all of the time. There are almost never fresh foods in McMurdo and all food (fruits, vegetables, starches, or meats) come from frozen or dried supplies. We all long for fresh foods, or “freshies” as they are endearingly called here.

Ashley choosing from the dinner options on the buffet. Photo by: Tandra Fraser

Sunday brunch is the best meal of the week and all the stops are pulled out for this one. We have been lucky this year to get fresh cream on two separate Sundays (a generous gift from the New York National Guard) to have with our coffee for Sunday morning. If any freshies did exist on station, we would probably see them at Sunday brunch (so far, no such luck).

Ashley getting her Frosty Boy dessert. Look how happy! Photo by: Tandra Fraser

I couldn’t write a blog post about food without talking about frosty boy. Frosty boy is a staple in the Galley and his job is to keep morale high. Yes, our soft serve ice cream machine, complete with sidekicks of myriad sundae toppings, we love him.

Dinner time in McMurdo, taken in the Galley dining area. Photo by: Ashley Shaw

Eating while doing fieldwork is a different story. If you are on a day trip, you have to pack a lunch and snacks to bring with you. There are supplies for this in the Galley, but you must choose them and pack your lunches yourself. If you are staying overnight in the field, it’s your responsibility to plan your own meals and you should arrange to pick up some frozen and dried goods – the choices are up to you! Most established field camps have an indoor area for cooking and eating.

Check back tomorrow for the 3rd and final “day in the life” post. I will tell you a little bit about where we live, sleep, and what we do every day around station!

Written by: Ashley Shaw

The community in McMurdo is pretty excited about science. After all, we’re all here to get science done in one way or another – either by supporting science activities or performing actual data collection. The McMurdo community loves to know what scientists are working on and what they are finding out. So, each week there is an organized Sunday Science Lecture. It’s held in the Galley and the whole station is invited to attend. This event is well loved and draws a big crowd.

Jeb Barrett (left) and Byron Adams (right) answer questions during the Sunday Science Lecture. This event is held weekly in the Galley. Photo by: Ashley Shaw

This past Sunday was a special Science Lecture, because it was given by some of our own teammates, Jeb Barrett and Byron Adams. Together, they gave a great talk about the major findings of the McMurdo Dry Valleys LTER, the ecology of the Dry Valleys and how this ecology has been changing over the past 25 years. The crowd was excited to learn about the nematodes, tardigrades, and rotifers that live in the valleys. Plus Jeb and Byron showed some cool videos of these awesome animals.

A female Eudorylaimus – one of the nematodes that lives in the Dry Valleys. Byron explained how certain nematodes (including this one), prefer wetter habitats. Photo by: Ashley Shaw

Jeb explained that due to increasing solar radiation and warmer temperatures, there has been increased melt from the glaciers, which has caused lake levels in the valley to rise. This increased melt affects the soil chemistry, moving salts and fine sediments across the landscape and altering soil nutrients. The increased melt and rising lake levels also has had an impact on science logistics. Structures from the permanent Fryxell camp have had to be moved away from the lake to avoid being engulfed by the rising waters of Lake Fryxell!

Increased melt water from glaciers flows through streams into the lake. Photo by: Ashley Shaw

Did you know that plants and animals (even dinosaurs!) used to live on the land that is now Antarctica? After the Pleistocene, the only animals that survived and still live in terrestrial Antarctica today are the very small ones: nematodes, tardigrades, rotifers, collembola, and mites. It’s pretty amazing that these animals survive the harsh conditions of Antarctica – cold, dry, dark (for half of the year), UV radiation (thanks, ozone hole), and salt. Byron told us about how the LTER is finding that the soil community is affected by increased moisture caused by melt from glaciers and permafrost.

Byron explains soil ecology of the dry valleys. Photo by: Ashley Shaw

After the talk, the crowd had lots of questions for Jeb and Byron. People wanted to know more about how nematodes and other animals survive in Antarctica (they go into a dormant state called anhydrobiosis when times get tough) and how long they live for (we aren’t sure, but at least decades!). They also were curious about how salty the soils are (pretty salty!) and where the carbon that fuels the foodweb comes from (lake and stream algae, cyanobacteria, and other maybe unknown sources). Overall, the talk was informative, entertaining, and really got people jazzed up about the McMurdo LTER science! Way to go, Jeb and Byron!

Written by: Ashley Shaw

Many researchers working in Antarctica study large things. The ice lakes and glaciers are so massive that the glaciologists who study them may find it easier to use airplanes rather than tons as unit of measure. Oceanographers and climatologists track down icebergs larger than some countries. Volcanologists are checking the vital signs of that formidable giant that is Mount Erebus (3794 m above sea level, more than 12 thousand feet). Astronomers look out of the clear Antarctic skies to stars and galaxies.

Many biologists study large and easily recognized creatures such as seals, penguins, and whales. But where we “Wormherders” are conducting research there are no living things that the naked eye can see. We are focusing on much smaller creatures, such as nematode worms. Virtually all soils on Earth host nematodes, but in the Dry Valleys very few species occur, and they are specially adapted to this extreme environment. The same goes for the microscopic algae and the bacteria living in lakes and soils that other teams in McMurdo are studying. Some of the most exciting ecological questions in Antarctica are about very small things indeed.

(Admittedly, even nematodes and microbes may be described as very large by the particle physicists working on “AMANDA”, the Antarctic Muon and Neutrino Detecting Array. There truly is science for all sizes at McMurdo.)

The McMurdo Dry Valleys seem as desolate and lifeless a place as one could conceive. But take a scoop of soil from almost anywhere in the valleys, subject it to an appropriate extraction process, put the resulting water solution under a microscope, and there you go: living creatures, more abundant and active than you might suspect.

Scottnema lindsayae, one of the most abundant residents of the McMurdo Dry Valleys. A female and a male caught in the act of mating. Photo by Jessica Trout-Haney

Some of us have been busy all day identifying and counting specimens from samples we collected last week. It’s not at all boring as some might suspect, partly because of the beauty of the organisms we look at. Nematodes bend, coil and stretch elegantly on the microscope plate. Scottnema lindsayae, the most abundant, performs what may look like some contemporary dance. Less common but hard to miss, the much larger Eudorylaimus antarcticus flexes slowly, like a microscopic python waking from sleep. A Plectus sp. with its head inside a dead rotifer, busy scavenging on bacteria inside the decomposing body, looks like it has put on a mask to scare the others around it.

Nematodes dominate this playground, but there is more. Rotifers scurry, hop and cartwheel across the plate like pesky children, sometimes playing tug-of-war with nematodes over lumps of organic matter. Even faster than rotifers, a ciliate slides effortlessly, in shape and motion somewhat similar to a flying saucer (or a swimming saucer). Tardigrades move clumsily on their short legs, but don’t be fooled by their cute appearance – they are some of the toughest creatures on Earth.

Some team members load scientific equipment and supplies on the helicopter that will take them from Lake Hoare Camp to another location in the Dry Valleys. Photo by Walter Andriuzzi

It was not an easy job to collect these biological samples. The helicopter is the only means on transport to get from McMurdo to the Dry Valleys. Flights have to be planned days in advance with the crew, but often they need to be rescheduled due to the unpredictable weather. Once in the Valleys, the Wormherders have to move fast to finish sampling before the helicopter returns (but it also helps against freezing).

Sometimes daily trips aren’t enough. Thankfully for us, there are a handful of well-equipped camping sites in the Dry Valleys. Last week we spent a night at Lake Hoare Camp, managed by Rae Spain and Renee Noffke – a homely, warm place in a land of ice giants and sharp winds. The landscape around the camp is so spectacular that some of our team, despite being quite tired from the day’s work, couldn’t resist the temptation of an after-dinner hike. We walked along Canada Glacier, past mummified seals and ice stalactites, and on to the moraine on the side of the glacier, and eventually we stepped on the glacier (with the appropriate footwear!).

Lake Hoare Camp, an important logistics base for researchers working in the McMurdo Dry Valleys. Photo by Walter Andriuzzi

There might seem to be a paradox – on one hand the size and majesty of the Dry Valleys, and on the other hand the minuscule beauty of the fauna that inhabits those soils. But such is the greatness of ecology, a science that connects the small and the large, the hidden and the obvious. With a bit of assistance from the weather, we’ll be collecting more samples from the Dry Valleys in the next few days, and who knows what surprises we might find under a microscope. In the meantime, some team members are camping near Lake Fryxell in Taylor Valley, taking care of one of the most exciting ecological experiments undergoing in Antarctica.

by Walter Andriuzzi

On 5 January 2016, two helicopters landed a team of researchers in a place that, at least geographically, is at the frontier of ecological science: the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica, the most remote of the Long-Term Ecological Research sites funded by the US National Science Foundation. The team, led by Dr. Diana Wall, Colorado State University (third from the left in the picture below), Dr. Byron Adams, Brigham Young University (fourth from the left), Dr. Ross Virginia, Dartmouth College and Dr. John Barrett, Virginia Tech, is studying the soil biological communities of a place unlike any other in the world.

Part of the 2015-2016 Soils Team near Many Glaciers Pond in Taylor Valley. (Top row (Left to right): Jess Trout-Haney, Ruth Heindel, Diana Wall, Byron Adams, Tandra Fraser, Dan Bransford; Front row (left to right): Xia Xue, Walter Andriuzzi).

Part of the 2015-2016 Soils Team near Many Glaciers Pond in Taylor Valley. (Top row (Left to right): Jess Trout-Haney, Ruth Heindel, Diana Wall, Byron Adams, Tandra Fraser, Dan Bransford; Front row (left to right): Xia Xue, Walter Andriuzzi).

Imagine you are in a huge valley surrounded by glaciers and ice-capped mountains. The silence is surreal, and the cold fierce. You are more than 10° further South than the Antarctic polar circle, a distance similar to that between England and Iceland. Summer time here means that the daylight is almost permanent – and so is the cold, relentless wind. Ahead of you there is a small lake that stubbornly refuses to freeze. Turn around, and you will see the mouth of a huge glacier, a wall of ice that puts any human fortress to shame. At first the glacier looks small and just a short walk away, but don’t be fooled, you may not reach it and come back in time for the helicopter to pick you up if the weather turns bad. Distances are deceiving in such an empty space.

There is no green for the eyes to rest upon, not even a patch of mosses or lichens. No bird songs, no buzz of insects. And yet – or perhaps because of it – everywhere the elements conjure up the illusion of noisy, visible life. A sudden ripple in the pond makes you think of a surfacing fish, but it was just the wind. Long lines of compacted terrain help you walk across the sandy surface, but they are the results of cracks made by the freezing and thawing of the permafrost, neither human nor animal feet had a role in making them. The wind carved some rocks in shapes of horns and turtles, but nothing moves except sand and dust.

The place seems utterly lifeless. But it’s not.

Minuscule animals live in the dry, saline soil spared from the grip of the ice that covers most of this strange continent. The nematode Scottnema lindsayae, a worm usually less than 1 millimeter long, is in many places the largest organism to be found. It can be surprisingly abundant, feeding on the even sturdier microbes and of whatever organic matter it can find (some of the latter perhaps thousands of years old). Invisible cyanobacteria on the surface manage to get enough energy from the UV-packed light of the ephemeral Antarctic summer to set a miniature food web in motion. Deep in the ice-covered lakes, communities of phytoplankton and bacteria thrive undisturbed.

The team at work in Many Glaciers Pond in Taylor Valley. Photo by Walter Andriuzzi

All these organisms are tough, superbly adapted to these hostile conditions. They can inactivate when it gets too cold, tolerate high salinity, cycle carbon and nutrients in a soil that has less organic matter than most deserts. But even these survivors are facing hard times. Human-induced climate change is making environmental conditions increasingly unpredictable. More freeze-thaw cycles impose physiological stress, and may lead to mismatches in the organisms’ responses to seasonal temperature fluctuations. Increasing ice-melting events and lake level rise across the valleys could be spreading some species at the expense of the dominant, dry-specialist ones. Lessons learnt from the McMurdo Dry Valleys may give hints on the fate of other, more complex ecosystems that are also shaped by an unforgiving environment and a changing climate.

The ongoing long-term ecological studies in this ecosystem have therefore two aims: to understand and protect one of the few truly pristine ecosystems left on Earth, and to generate ecological knowledge that will feed into broader research issues.

by Walter Andriuzzi